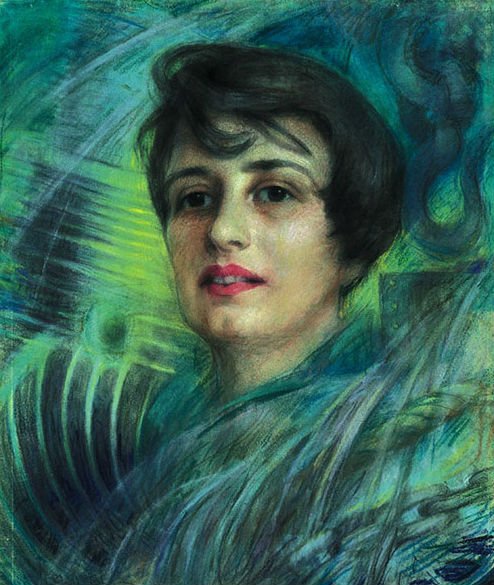

How to Write About Ayn Rand

Her nuance is often brushed over in broad, unfounded strokes.

The criticism of Ayn Rand says more about our culture than it does about her.

***

I am not an Objectivist any more than I am a Nietzschean, an Aristotelian, a Hugoean, or a Joseph Campbellian. Rand’s philosophy was a piece of my intellectual development, but I wouldn’t define myself by it. Sure, one of my favorite scenes in any book can be found in The Fountainhead. And We the Living is, in my opinion, less a novel and more a textbook on characterization. It is also my opinion, however, that Atlas Shrugged is indeed the steaming pile of heavy-handedness that critics make it out to be.

This is to offer some context and perhaps some credence when I make this claim: Nobody is denigrated more unduly, and with more impunity, than Ayn Rand.

You’d think the feminists on the Left would throw her a bone simply because she’s a woman, but they don’t—which, if nothing else, indicates the true aim of feminism. If equality was it, then they would love Rand as unduly as conservatives love Candace Owens.

And the Right, well, they use Rand for an intellectual defense the way the Nazis used Nietzsche. If you think this means conservatives are like Nazis and Rand is like Nietzsche, then please stop reading now. The ideas in this article are too advanced and you’re only going to end up hurting yourself with them.

As with most unfounded criticism, it isn’t well thought-out so it ends up being a rehash of itself. This is especially true with the criticism of Rand, which at least makes it possible to dispel in one article.

Here are the ideas that people get wrong over and over again when writing about Ayn Rand.

Misconstrue altruism and selfishness

Nothing indicates you’ve barely read three pages of Rand than when you think Rand’s use of “altruism” is the common usage. She doesn’t mean helping people or benevolence, and that’s exactly the point she made with that word.

“Altruism” is a victim of conflation. Sometimes, when people use that word, they mean “benevolence.” Though other times, people mean “sacrifice yourself for the good of others.” These are two completely different definitions, and the fact that we use the same word for both demonstrates the intellectual laziness around such an important distinction.

Rand makes this clarification on page two, literally, of her seminal essay on ethics, which goes to show the dearth of curiosity from her critics.

The same goes for “selfishness.” She uses this word for the same reason she criticizes altruism. Sometimes, when people use the word selfish, they mean “a healthy respect for your self-interest.” Yet people also use it when they mean “a narcissistic harm of others for your own benefit.” Again, we have two different kinds of selfishness subsumed under the same word. Therefore, her use of that word is meta in that she makes a point about the vital nature of definitions simply through her use of it.

This is what I’ve done with Animus. The word literally means male soul. So why has it become associated with vengeful, maladaptive hatred? It indicates a philosophical trend in Western Civilization ever since the development of Stoicism and then its evolution into Christianity. It indicates that emotions are inherently irrational, so we never learn how to manage them. The only thing we can do with an emotion is either to repress it or vent it. Therefore, when I take back the word Animus as a concept, I make a meta point about the nature of emotions.

Also, “animus” is a nod to Jung to indicate the influence he has had on my thought—though I wouldn’t call myself a Jungian, either.

Drop context about the blank slate

A perhaps more intelligent criticism of Rand is one of her blank slatism—the idea that all knowledge comes from sense perception. This seems like a just criticism because the blank slate has been long demonstrated to be incorrect.

But to understand Rand’s actual point, we need to first understand the context in which she defended the blank slate, which was back in the 60s before the social constructionists insisted that men and women were the same biologically—before they insisted the only reason men desire young, beautiful women is because of culturally ingrained misogyny. She in no way critiqued the idea that our mind had a specific nature. What she criticized is the philosophical notion that ideas, or concepts, are imbued on us from birth. This is the Platonic-Kantian view that presents ideas as an inherent part of our mind rather than products of observation.

My bet is that if Rand was alive today, she would have a lot of disagreement with evolutionary psychology. She may be incorrect in some of this disagreement but it wouldn’t matter because she wasn’t a psychologist. Regardless, there is indeed a lot wrong with evopsych—for a survey of these wrongs, my article on the limits of evolutionary psychology.

Conflate objective with absolute

The stupidity of this point first hit me in the face while reading Michael Shermer’s book on why smart people believe stupid things. In it, his criticism of Objectivism was such a blatant straw man that I thought it must’ve been a joke. He asserts that Objectivists believe in absolute right and wrong—that an action can be either entirely correct or entirely incorrect. Ethics, Shermer says, has more to do with context of that action than anything else—which is correct. Too bad for Shermer, this is exactly what Rand means by “objective.” She uses this word to distinguish it from both “absolutism” (what Shermer criticizes) and “subjectivism.” In fact, Rand criticizes absolutism in ethics as much as she criticizes subjectivism. Again, Shermer and every other critic would know this if they read more than two sentences of her nonfiction.

Criticize rape scenes

When a bunch of liberal women get together and admit they want to be raped, it’s called third-wave feminism. But if a woman who disagrees with Leftism also insinuates her own, similar fantasy through the portrayal of a fictional character, then it somehow invalidates everything else she says. Why? Refer back to the ultimate point of feminism.

Mock her view of emotions

It’s true—Rand didn’t understand emotions. She wrote her characters as if intelligence and wisdom were the same thing—as if the mere intellectual grasp of a concept was enough to make them act in line with that concept. But again, she wasn’t a psychologist and she didn’t pretend to be. We may as well criticize Salvador Dali for his views on pastrami sandwiches. Besides, every critic of Rand doesn’t understand emotions either. The most they understand is that people are emotional, which isn’t even close to the same thing.

Accuse Randians of being annoying

The only people who are more annoying than Randians are those who think ad hominems (derivative ones at that) are valid forms of argument.

Conclusion

You don’t need to agree with Rand or even like her. The point is that the way in which we criticize Rand’s ideas is a model for how we criticize all new ideas. Any worldview that’s truly revolutionary won’t require us to think about new ideas in old ways—rather, it requires that we think about old ideas in new ways.